Theoretical Misconceptions in Microwave Film Absorption and Conductivity Relations

Systemic Theoretical Errors in Microwave Absorption Research and the Decline of Theoretical Rigor in Modern Academia

Preprint

Liu, Yue, Theoretical Misconceptions in Microwave Film Absorption and Conductivity Relations (October 25, 2025). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5656670 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5656670

Systemic Theoretical Errors in Microwave Absorption Research and the Decline of Theoretical Rigor in Modern Academia

Theoretical Misconceptions in Microwave Film Absorption and Conductivity Relations

Yue Liu

College of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Shenyang Normal University, Shenyang, P. R. China,110034, yueliusd@163.com

ORCID: Yue Liu: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5924-9730

Abstract: Recent analyses highlight pervasive theoretical errors in fields ranging from microwave absorber design to optical conductivity characterization. In microwave absorption research, Liu et al. (2025) systematically review decades of literature and identify fundamental confusions in thin-film absorber theory. They show that the film’s input impedance (Zin) has been erroneously equated with the bulk material’s characteristic impedance (ZM), and that the film’s reflection loss has been misinterpreted as if it were the film’s interface alone. These mistakes led to a flawed “impedance matching” theory, which wrongfully ascribes film-thickness effects to intrinsic material resonances. Instead, the correct wave-mechanics description treats absorption peaks as arising from interference (wave cancellation) in the film rather than from material resonance. In parallel, Aly (2022) exposes a widespread misuse of textbook formulas relating electrical and optical conductivity. He demonstrates that several published papers have propagated incorrect relations (e.g. σel = 2kσop/α) and provides the correct expressions, noting that yet another contemporary paper also fell prey to this error. Both case studies exemplify a larger trend: a growing “theoretical poverty” in modern research where experimental results are published without sufficient theoretical validation. As Liu (2025) observes, such errors are often “correctable with undergraduate-level physics,” yet the community frequently ignores published corrections and persists in error. This review discusses the nature of these two examples, the corrections proposed, and their implications for scientific rigor and methodology.

Keywords: microwave absorption film, impedance matching theory, thin-film vs bulk, optical conductivity, electrical conductivity, experimental bias, scientific methodology, theoretical validation, wave cancellation, reflection loss.

1. Microwave Absorber Films: Theory vs. Misconceptions

Liu et al. (2025) survey the literature on thin-film microwave absorbers and find that systematic mistakes have been baked into common practice[1]. In a typical setup, a lossy film of thickness d is backed by a perfect conductor. The correct analysis (transmission-line or wave-interference theory) yields an input impedance for the film and a corresponding reflection loss. However, many papers conflated with the bulk material’s characteristic impedance , treating the film as if it were an infinite slab of that material. In fact, Liu et al. stress that film and material are fundamentally different[2, 3]: they write that “film, interface, and material are all different”[4] and note that “the interface does not absorb microwaves” on its own[5]. Only when (impedance matched to free space) do all incident waves enter any absorber [6]. By contrast, setting (the so-called impedance-matching condition used in some analyses) does not guarantee full penetration, because it ignores the presence of two counter-propagating beams inside the film. In short, the classic “impedance matching theory” was misinterpreted: Liu et al. show that claiming perfect matching at mistakes the film’s response for that of the material[7].

Liu et al. identify several specific confusions:

Zin vs. ZM: The film’s input impedance

was often treated as if it were the material’s characteristic impedance

. In reality only

ensures all energy enters the film, while

is merely a partial condition.[6, 8]

Reflection coefficients: The reflection coefficient of the interface (s11) was confused with the film’s total reflection loss.[1] Liu et al. emphasize that the front interface by itself “never absorbs microwaves”[5]. Thus using only the interface impedance to predict absorption is incorrect.

Wave interference vs. resonance: Traditional quarter-wavelength arguments treated absorption maxima as if they were material resonances.[9, 10] Liu et al. clarify that in a metal-backed film the observed peaks are actually due to wave cancellation between the front-surface reflection and the multiple internal reflections (beams r1 and r2)[11-13]. In their words, “the absorption peaks originate from wave cancellation instead of the innate properties of material”.[14, 15]

These corrections have major consequences. The old “impedance matching theory” predicted that absorption peaks should occur whenever , attributing any offset to reduced penetration. But Liu et al. show that all energy can only enter the film when (i.e. ), and that the film then “behaves like [a] material” with no additional absorption peak as thickness increases[7, 16]. In fact, their analysis (via proper wave mechanics) demonstrates that the peak shifts with thickness according to interference conditions, not due to changing material parameters. The flawed theory had even argued that the film peak was a quarter-wave resonance of the material; Liu et al. counter this by showing it is purely geometric interference.

In summary, the review shows that decades of work have mistakenly applied bulk-material thinking to thin films. These errors “have not been corrected over many years”, and have been propagated through thousands of publications[1, 17]. Liu et al. note that despite the availability of a “new wave mechanics theory” of film absorption, many researchers still use the old models. They use transmission-line derivations and energy conservation to establish the correct formulas for metal-backed films (beam superposition and reflection loss),[14] and tabulate how those resolve the misconceptions.[12] Their conclusion is that the film’s microwave absorption must be understood via interference of two beams (front-surface and internal reflection) – a mechanism fundamentally different from simple material resonance. They also note that a film’s interface cannot on its own absorb energy[5], so analyses must treat the film-layer as a whole.

2. Optical vs. Electrical Conductivity Relations

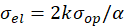

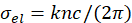

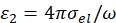

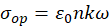

In a parallel vein, Aly (2022) [18] surveys the literature on optical characterization and finds a remarkably similar pattern of theoretical oversight. He reviews a series of papers (mostly in J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. and related journals) that purported to relate a material’s DC electrical conductivity () to its optical conductivity () via simple formulas involving the refractive index , extinction coefficient , absorption coefficient , and wavelength . For instance, some authors had used formulas like or . Aly demonstrates that these expressions are mathematically incorrect. By starting from the standard definitions ( in CGS units, etc.) and using the exact relationships between optical constants, he derives the true relations and shows the published ones do not hold. In his own words, he shows that the recently used equations “are incorrect” and must be abandoned.

Aly’s comment enumerates dozens of affected references. He explicitly lists many recent studies ([1–90] and beyond) where the wrong formula has been propagated, across multiple journals (Materials Today, RSC Advances, Opt. Commun., etc.). At the end of the proof stage he adds a note: “The author has noticed that another paper [122] that just became available during the proofs has also used the wrong equation in Eq. (19)”. Reference [122] itself is a 2022 J. Alloys Comp. paper. In total, including this note, Aly’s survey covers on the order of a hundred published works with the same “textbook-level” mistake. The implication is clear: a basic unit conversion or formula from elementary optics has been ignored by many researchers, leading to widespread errors in reported conductivity plots and derived conclusions.

Aly’s work corrects the theoretical relationship and emphasizes rigor: he provides the correct expressions (e.g. using in SI units, properly relating it to ) and advises the community to stop using the incorrect formulas. Importantly, he does not just issue a correction; he shows that the flawed equations yield nonsensical behavior if plotted (e.g. absurdly high conductivities at low photon energies). His approach is purely analytical, drawing on well-known textbook physics. He frames it as a textbook oversight rather than an experimental ambiguity: “the difference between the optical and electrical conductivities is considered and analyzed through well-known textbook considerations”. This elevates the error from a niche oversight to a sign of a larger methodological issue.

3. Broader Implications for Scientific Methodology

Both case studies (Liu et al. on microwave films, and Aly on conductivity) point to a common theme: the neglect of fundamental theory can allow serious errors to persist in the literature. Liu (2025) explicitly discusses this under the concept of “theoretical poverty” in modern science.[19] He notes that despite the existence of simple physics explanations (“correctable with undergraduate-level physics”), the community repeatedly overlooks them. Specifically, Liu finds that even after posting correction papers, many authors do not revise their models or citations.[20] He writes that “material scientists have become accustomed to use these wrong theories and continued to adopt them”[1], and that the field behaves like Feynman’s “cargo cult science”[21, 22] – maintaining the appearance of rigor while ignoring fundamental principles. Liu documents that high-impact journals have published the flawed theories, and that follow-up comments and reviews often go unnoticed as research proceeds.

Aly’s commentary similarly reflects an over-emphasis on data over analysis.[23] His critique implicitly echoes the empirical orthodoxy critiqued by Liu (2025), who argues that modern research often puts experimental novelty ahead of theoretical consistency[24, 25]. Aly points out that authors simply applied a formula (perhaps derived empirically or memorized) without re-deriving it, and then drew conclusions from plots of “electrical conductivity” vs. photon energy based on that misuse. This mirrors Liu’s warning that we have reversed the traditional scientific hierarchy: experiments should test theory, not produce it[24]. In Aly’s case, the experiments (optical spectroscopy) were interpreted through the lens of a faulty equation, leading to spurious results.

These phenomena tie into the larger “replication crisis” and bias critiques in science. While not focused on statistical issues per se, both studies underscore a bias towards publishing sensational experimental findings and a neglect of peer review of mathematical correctness. As Liu et al. (2025) show, thousands of papers used the old impedance-matching idea, and even the corrected theory is slow to propagate[1, 17]. Aly shows a parallel in a completely different subfield. Together, they support arguments in recent meta-scientific literature that academia undervalues theory. Liu (2025) observes that when theoretical checks are absent, “fundamental theoretical errors persist in high-impact publications”[24] and warns of a growing “crisis in scientific literacy” as a result[19]. He also notes that publishing practices and review priorities often fail to catch these elementary errors, effectively rewarding novelty over correctness.

In concrete terms, the microwave and conductivity examples illustrate the need for more thorough peer review of theory. Journals and researchers should verify that used equations and models are dimensionally consistent and physically justified. Review articles, in particular, ought to go beyond balance (simply summarizing experiments)[25] and actively seek theoretical insight[24, 26]. The case of the conductivity formulas also suggests that even “Letter” publications, often rapidly peer-reviewed, may slip in errors if experts on fundamentals are not consulted.

4. Conclusion

The focused reviews by Liu et al. and Aly reveal how easily widespread misconceptions can become “entrenched” in scientific fields.[27] In thin-film microwave absorption, decades of work were based on an incorrect interpretation of impedance and reflection, until systematic wave-mechanics analysis corrected the record [15]. In optical conductivity, a simple algebraic mistake propagated through scores of experimental papers until Aly’s comment shut down the confusion. These examples underscore that basic theoretical checks are crucial: they can catch errors that no amount of experimental data would reveal by itself. As Liu (2025) argues, science must remember that theory provides the ultimate test of empirical results. Moving forward, integrating clear theoretical modeling with experimental work—and encouraging review articles to emphasize conceptual innovation [28, 29]—will help ensure that such fundamental mistakes are identified early and corrected. In the words of Liu et al., researchers should “stop using” the old theories and embrace the correct wave-mechanics view of thin-film absorption. Likewise, following Aly’s admonition, the community must “discontinue” the misuse of conductivity relations and adhere to the proper textbook formulas. Only by valuing theoretical rigor as much as experimental ingenuity can science avoid lapsing into the “cargo cult” of unexamined methods.

References

1. Liu, Y., Y. Liu, and M.G.B. Drew, Recognizing Problems in Publications Concerned with Microwave Absorption Film and Providing Corrections: A Focused Review. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 2025. 64(7): p. 3635–3650.

2. Liu, Y., et al., Reflection Loss is a Parameter for Film, not Material. Non-Metallic Material Science, 2023. 5(1): p. 38 - 48.

3. Liu, Y., Liu,Ying, and M.G.B. Drew, The Fundamental Distinction Between Films and Materials: How Conceptual Confusion Led to Theoretical Errors in Microwave Absorption. 2025.

4. Liu, Y., Y. Liu, and M.G.B. Drew, Review of Wave Mechanics Theory for Microwave Absorption by Film. Journal of Molecular Science, 2024. 40(4): p. 300-305.

5. Liu, Y., Y. Liu, and M.G.B. Drew, A Re-evaluation of the mechanism of microwave absorption in film – Part 1: Energy conservation. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 2022. 290: p. 126576.

6. Liu, Y., et al., An experimental and theoretical investigation into methods concerned with “reflection loss” for microwave absorbing materials. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 2020. 243: p. 122624.

7. Liu, Y., M.G.B. Drew, and Y. Liu, A physics investigation of impedance matching theory in microwave absorption film— Part 2: Problem analyses. Journal of Applied Physics, 2023. 134(4): p. 045304.

8. Liu, Y., et al., Microwave absorption properties of Ag/NiFe2-xCexO4 characterized by an alternative procedure rather than the main stream method using “reflection loss”. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 2020. 243: p. e122615.

9. Hou, Z.-L., et al., A perspective on impedance matching and resonance absorption mechanism for electromagnetic wave absorbing. Carbon, 2024. 222: p. 118935.

10. Cheng, J., et al., Emerging Materials and Designs for Low‐ and Multi‐Band Electromagnetic Wave Absorbers: The Search for Dielectric and Magnetic Synergy? Advanced Functional Materials, 2022. 32(23): p. 2200123.

11. Liu, Y., Y. Liu, and M.G.B. Drew, A theoretical investigation on the quarter-wavelength model — Part 1:Analysis. Physica Scripta, 2021. 96(12): p. 125003.

12. Liu, Y., Y. Liu, and M.G.B. Drew, A theoretical investigation of the quarter-wavelength model-part 2: verification and extension. Physica Scripta, 2022. 97(1): p. 015806.

13. Liu, Y., Y. Liu, and M.G.B. Drew, Wave Mechanics of Microwave Absorption in Films: Multilayered Films. Journal of Electronic Materials, 2024. 53: p. 8154–8170.

14. Liu, Y., Y. Liu, and M.G.B. Drew, A Re-evaluation of the mechanism of microwave absorption in film – Part 2: The real mechanism. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 2022. 291: p. 126601.

15. Liu, Y., Y. Liu, and M.G.B. Drew, Wave mechanics of microwave absorption in films: A short review. Optics and Laser Technology, 2024. 178: p. 111211.

16. Liu, Y., M.G.B. Drew, and Y. Liu, Theoretical insights manifested by wave mechanics theory of microwave absorption—Part 1: A theoretical perspective. Preprints.org, 2025.

17. Liu, Y., Y. Liu, and M.G.B. Drew, Citation Issues in Wave Mechanics Theory of Microwave Absorption: A Comprehensive Analysis with Theoretical Foundations and Peer Review Challenges. arXiv:2508.06522v2, 2025.

18. Aly, K.A., Comment on the relationship between electrical and optical conductivity used in several recent papers published in the journal of materials science: materials in electronics. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics, 2022. 33(6): p. 2889-2898.

19. Liu, Y., The Theoretical Poverty of Modern Academia: Evidence of Widespread Intellectual Decline in Contemporary Scientific Research. SSRN, 2025.

20. Liu, Y., Self-Citation Versus External Citation in Academic Publishing: A Critical Analysis of Citation Reliability, Publication Biases, And Scientific Quality Assessment. SSRN, 2025.

21. Hanlon, M., Cargo Cult Science. European Review, 2013. 21(S1): p. S51-S55.

22. Feynman, R. Cargo Cult Science, From a Caltech commencement address given in 1974. 1974; Available from: https://sites.cs.ucsb.edu/~ravenben/cargocult.html.

23. Liu, Y., The Misapplication of Statistical Methods in Liberal Arts: A Critical Analysis of Academic Publishing Bias Against Theoretical Research SSRN, 2025.

24. Liu, Y., Theoretical Primacy in Scientific Inquiry: A Critique of the Empirical Orthodoxy in Modern Research. SSRN, 2025.

25. Liu, Y., Rethinking “Balanced View” in Scientific Controversies: Why Fairness Is Not Equivalence Between Correct and Incorrect Theories. 2025.

26. Liu, Y., The Primacy of Theoretical Foundations: Why Textbooks and Monographs Matter more than Journal Literature in Scientific Progress. SSRN, 2025.

27. Liu, Y., The Entrenched Problems of Scientific Progress: An Analysis of Institutional Resistance and Systemic Barriers to Innovation. Preprints.org, 2025.

28. Liu, Y. and Y. Liu, Redefining Review Articles: Beyond Balance Toward Theoretical Innovation. SSRN, 2025.

29. Liu, Y., Scientific Accountability: The Case for Personal Responsibility in Academic Error Correction. Qeios, 2025: p. Preprint.